Can you hear me now?

How the inner ear's sensors are made

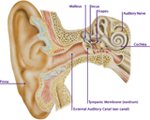

A UCLA study shows for the first time how microscopic crystals form sound and gravity sensors inside the inner ear. Located at the ends of cilia — tiny cellular hairs in the ear that move and transmit signals — these crystals play an important role in detecting sound, maintaining balance and regulating movement.

Dislodged ear crystals are to blame for the most common form of vertigo. Known as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, the disorder plagues up to 10 percent of people older than 60 and causes 20 percent of patients' dizziness complaints.

"People have known for a long time about the importance of cilia for propelling sperm up the uterus and moving mucus out of the lungs," said Kent Hill, associate professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the UCLA College of Letters and Science. "Our study illustrates that cilia perform many additional jobs that are essential to how our bodies develop and work."

"While it's been suggested that cilia movement contributes to the formation of ear crystals, this idea had never been tested before," he said. "Our findings show that cilia in the ear do move and demonstrate that cilia movement is needed for ear crystals to assemble in the right place."

According to Hill, the findings offer promise for the treatment of patients with hearing disorders and people with ciliopathies, disorders marked by poor cilia function. These conditions include sperm-related infertility, polycystic kidney disease, lung and respiratory disorders, swelling of the brain, and reversal of the internal organs' sites from one side of the body to the other.